When it comes to brain function and injury, medical terminology can be a language foreign to just about everyone. Most people simply don’t chat about neurons, dendrites, axon terminals, neurotransmitters, and excitotoxicity around the office water cooler or over breakfast with the family. A good brain injury lawyer certainly knows that. An experienced brain injury lawyer also knows he/she must talk with a jury and not at a jury and certainly not “over their heads” about the brain. The question is how to do that? How to make simple something so complex? The answer lies in breaking it down and making it real.

– Charlie Waters

Breaking It Down

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

– Albert Einstein

When presented correctly to a jury, a brain injury trial can be a fascinating, exciting, and even compelling journey of enlightenment. When done right, there’re lots of “Wow, I didn’t know that!” moments about brain function, and the even-more-important instances when “the light comes on” about the nature, extent, and mechanism of the injury. When these moments occur there’s a knowing acknowledgment from a jury you can see and feel. These are powerful, palpable experiences in a courtroom when a trial lawyer knows critical information is getting through and being understood.

When we present a case, we want our juries to know and genuinely understand the nature of your injury and why it’s causing such difficulty and hardship in your life. That’s because we know from experience an informed jury is a winning jury.

We all need guidance to understand something as wondrously complex as the human brain. Breaking it down simply means taking unfamiliar brain terminology and recasting it in ways and terms we can all relate to and better understand. We know that something is always like something else. In a brain injury trial, we seek to break the complexity down by speaking in terms of the “something else” through use of metaphors, similes, and analogies.

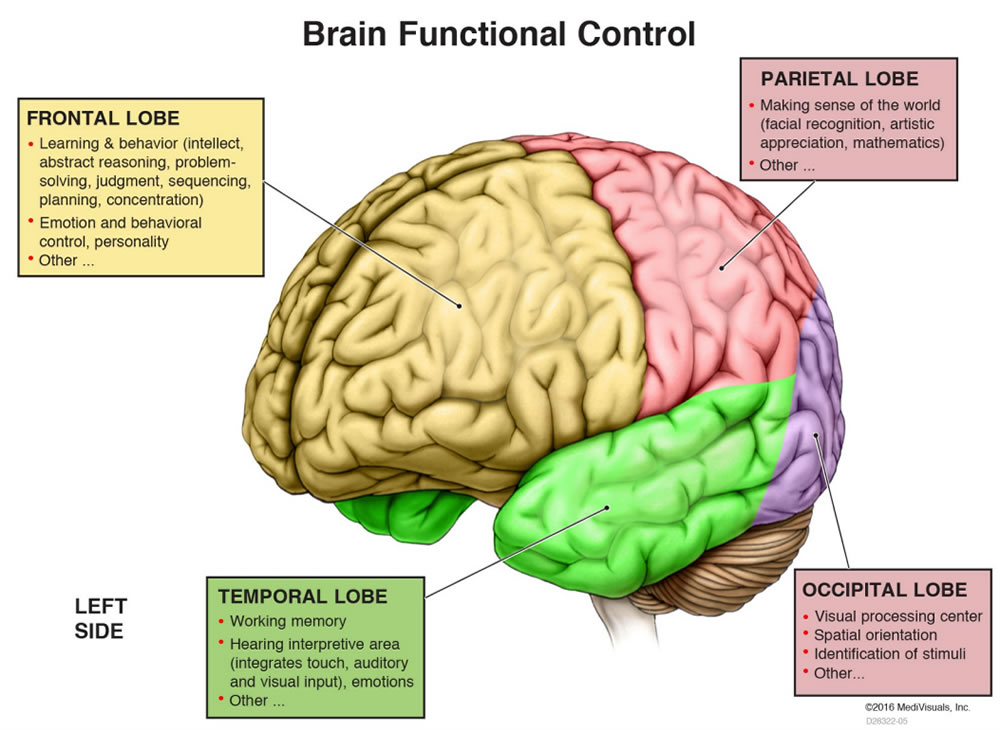

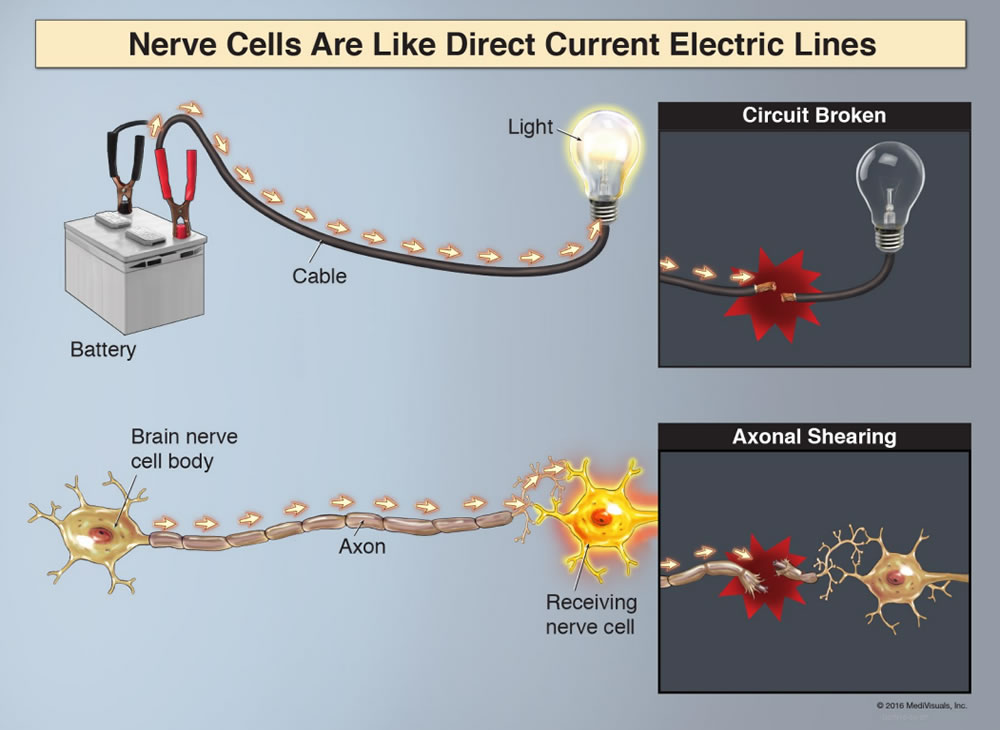

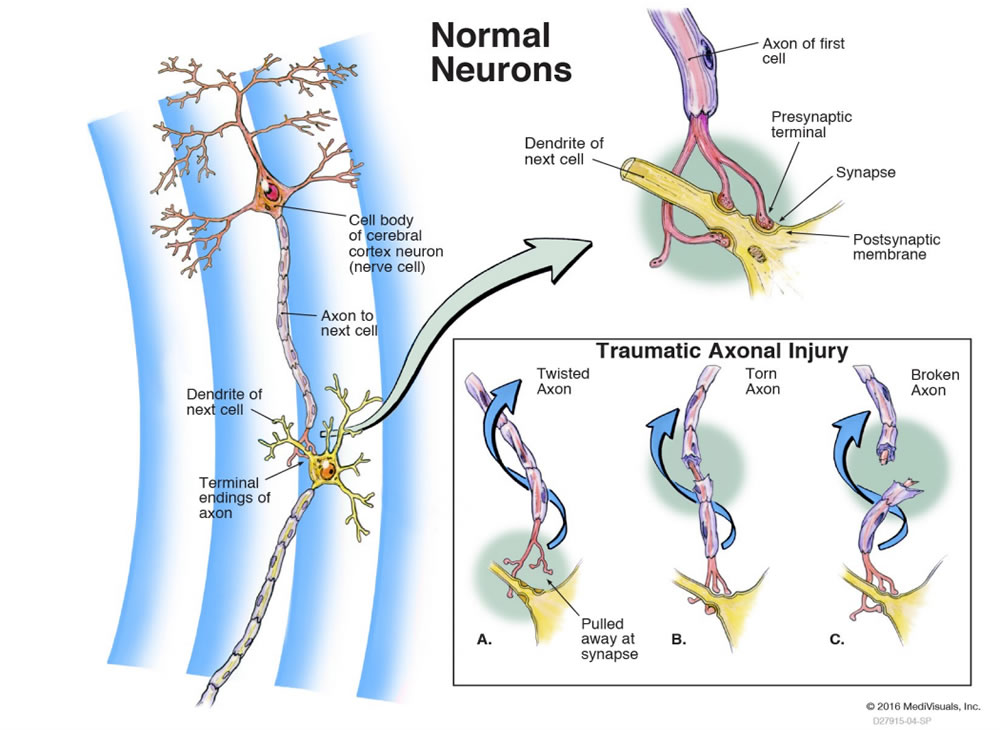

The brain is an “engine.” Neurotransmitters are the “oil for the engine” which must be maintained at proper levels. Neurons are “the critical wiring inside the engine.” Neurotransmission in brain function is the sending of messages like “the sending of electricity through wires on a telephone pole.” The amygdala is the brain’s “file cabinet where memories are stored.” The thalamus serves as “the brain’s switchboard by routing incoming messages” to the correct parts of the brain for processing. A sheared axon is “a broken wire.” Diffuse axonal shearing followed by excitotoxicity is “a mass of broken wiring leading to widespread injury across the brain’s playing field.” A brain neuron has a certain structure with a “head attached to an extended wire with tentacles on the end like those of an octopus.” That’s much better than saying a neuron has a soma attached to an axon terminal with extended dendrites.

Metaphors, similes, and analogies are figures of speech that transform words into memorable themes. They are thoughts in image form. They are not puzzles or a way to convey hidden meanings, but a way to let you know or feel something differently. They give words a way to go beyond their own meaning. They perform the art of resemblance to things known and understood. These are the best friends of a brain injury trial lawyer in turning encyclopedic brain words into kitchen-talk expressions everyone can relate to.

During a brain injury trial, numerous experts will be called to offer testimony on a wide range of issues. Front and center will be the medical experts called to talk about all aspects of the injury itself. Medical experts must communicate to a jury in understandable ways, and frankly, many struggle with it. Doctors tend to speak like they’re talking to other doctors. That doesn’t work in a courtroom.

When we present a case, we help our testifying medical experts break it down by turning them into classroom professors. Here’s a technique we often use to create a learning environment in the courtroom. When a medical witness first takes the witness stand, we set the stage with something like this:

Question: Dr. Reynolds, you are the primary treating physician to Susan Johnson for her brain injury, is the correct?

Answer: Yes.

Question: Before we discuss what happened to Susan, I think we could all benefit from a little education. I’d like for you to educate us on the brain; it’s various parts, how the brain is organized, how it communicates with itself and the rest of the body, and how the brain performs its many amazing functions. In other words, I think we could all benefit from an anatomy lesson. Can you help us with that?

Answer: Sure.

Question: Great! How about we pretend this courtroom is a classroom with you as the professor and the rest of us as your students? You lead the class and teach us about the brain so we can better understand what happened to Susan. Does that work for you?

Answer: Yes, and I’d be glad to.

Question: Very good doctor, but here’s the thing… and this is important. We need you to keep your lesson simple. We need you to break things down in ways we can understand them. We need you, whenever possible, to speak in lay terms we can relate to. None of us here went to medical school, so walk us through the brain using words we know. Talk to us like we’re smart, because we are, but just not as familiar with the subject as you . We want to learn from you, so don’t lose us along the way. Can you do that?

Answer: I think I can do that. Let’s give it a try.

By introducing the testifying physician in this way and setting the “classroom stage” for his testimony, we accomplish several things. First, we’ve let the jury know we empathize with them and the coming challenge. Our hope is they can now relax a bit and know that what’s coming won’t be over their heads. Even more important is the bond we’re starting to establish.

We’ve sent the clear message that we know the subject matter at times won’t be easy, but we’re going to do everything we can to make it understandable. That whenever we can, even with the testimony of medical experts, we will try to break it down and keep it simple. That builds credibility and trust. The jury starts to look to us for answers to the complex questions. They start to feel “we’re in this thing together.” A sense of camaraderie develops. A partnership begins to form with a common purpose towards a common goal…the full and appropriate compensation for our client. This can be a very powerful and positive bound that lasts throughout the trial, and beyond, when the jury makes its final decision.

Making It Real

“If trial litigation is the art of persuasion, demonstrative tools are the practitioner’s most powerful brushes.”

– Unknown

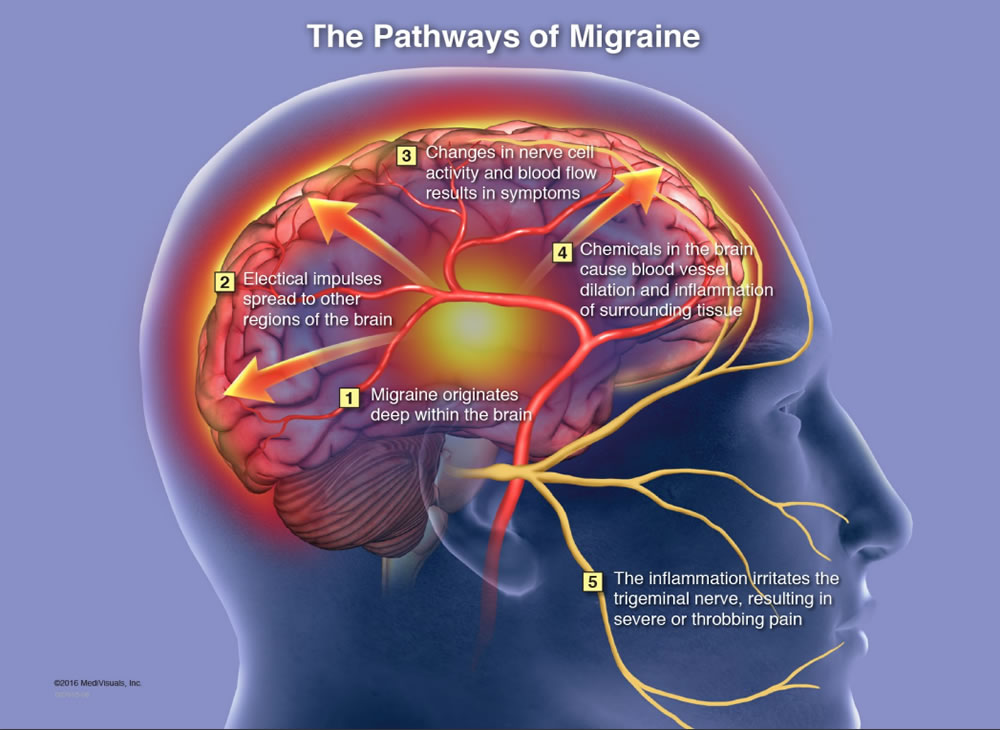

Medical illustrations, animations and imagery visualizations are critical to the successful presentation of a brain injury case. More than any other type of injury, the complexity involved cannot be adequately explained with just words. The dynamics of the many mechanisms of brain injury do not lend themselves to mere verbal concepts and descriptions. Much of the tissues involved are microscopic in size and something completely foreign to the average person. Certain things just must be “seen.” We understand that. Seeing is interesting. Seeing is fun. Seeing is believing. Seeing makes it real.

Our technological world has become accustomed to visual stimulation, colorful imagery and instant gratification. People, including jurors, want to be entertained and can lose focus, tune-out, and simply forget things not presented with a visual component. On average we only retain about 15% of what we hear audibly, however, retention climbs to 65% when the information is delivered visually. A good brain injury lawyer knows this and wouldn’t think of trying a brain injury case without a feast of illustrations and demonstrative aids. Numerous such medical illustrations can be found in this website in various sections located in the Texas Brain Injury Law Center database which we encourage you to view and read about.

A brain injury trial should include basic illustrations of brain anatomy presented early in the case to generally orient the jury on the structures and components involved, followed by case-specific illustrations and images of the client’s injury.